Building “Your World Last Week”: Something my son may benefit. Not sure if anyone else will.

Or: I Built a News Publication for My Son Using AI. One Tool Worked. One Didn't.

There’s a specific smell I remember from Sunday mornings in Chennai during the 1990s. Filter coffee, of course—that’s a given in any Tamil household. But also newsprint. That particular industrial ink smell of The Hindu or Indian Express spread across our dining table, its pages still slightly damp from the morning delivery.

My father or my mama would claim the front page and editorial section. I’d immediately grab sports (this was peak Sachin Tendulkar era, after all). And somewhere between arguing about who got the magazine supplement and why the comics page was thoroughly enjoyable, I absorbed something crucial: the world existed beyond our street, our city, our immediate experience. And … side note, if it was a Saturday morning, it was the Young World, exclaimed Ramya Ramaswamy. That reminded me of Gokulam and penpals through Gokulam. I believe a separate article is warranted for Newspapers and Magazine from the bygone era that talks about sections such as Know Your English, Editorial, Opinions, or even Spaced Out.

Image courtesy: The Hindu

Fast forward thirty years. I’m in Stouffville, Ontario. No cable TV at home—a deliberate choice in the streaming age. I get my news through the New York Times app, Google News, Facebook feeds, Hacker News, and conversations with friends. But my eleven-year-old son? His primary source of world knowledge is whatever makes it into his classroom.

This is a kid who, at any given moment, has four or five novels scattered around the house. Who plays Kerbal Space Program and can explain orbital mechanics better than I can. Who’s observant, curious, and loves reading.

But he has no equivalent of a newspaper experience.

The Gap I Didn’t Know Existed

I stumbled into this realization during a parent-teacher conference. I mentioned—probably complaining, if I’m honest—that my son seemed unaware of major world events. His teacher, Ms. Kim, introduced me to something called What in the World? from LesPlans—a Canadian teacher resource that presents current events in age-appropriate, curriculum-connected formats.

It was brilliant. Exactly what I wished existed when I was that age. And then I thought: Why not create something similar for my son? I could have subscribed to them, but they produce just 8 issues in a year.

Physical newspapers here are rare (because we made it so - our consumption patterns have shifted that killed these fantastic visual stimulants) and expensive. The economic model that supported my childhood Sunday ritual has collapsed. But the need for informed young citizens hasn’t disappeared. If anything, it’s more critical than ever.

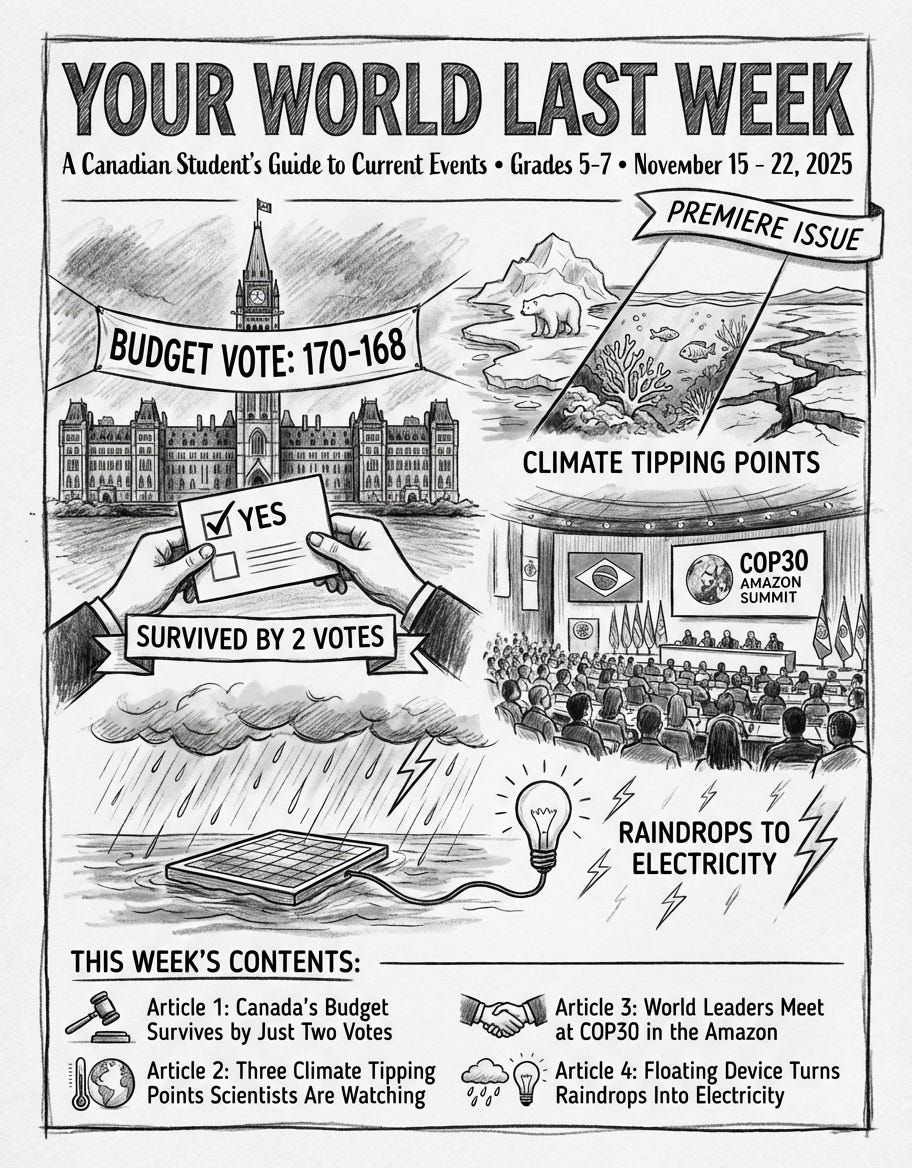

So I decided to build Your World Last Week—a weekly news publication designed for Canadian students in grades 5-7.

Enter the AI Helpers (and Their Various Degrees of Helpfulness)

Here’s where this story gets technical and, frankly, a bit frustrating.

I started with Gemini 3. Google had just released it with much fanfare—”the next best thing ever,” according to the marketing. It had access to current information, they said. It could search the web in real-time, they promised.

Requesting Claude for detailed prompt:

Gemini 3 thinking about date:

My plan was straightforward: Ask Gemini to research recent news from November 2025, focusing on stories relevant to Canadian middle schoolers. Politics, science, environment, technology. The kind of content that would spark curiosity and build critical thinking.

What could go wrong?

Everything. Everything Could Go Wrong.

Despite explicitly asking for November 2025 news, Gemini kept pulling information from April 2025. When I corrected it—politely at first, then with increasing exasperation—it would apologize and then... do the exact same thing again.

The conversation went something like this:

Me: “This section is incorrect. I specifically asked for November, you retrieved details from April. Poorly done. Redo that section again. Think again - it is November 2025.”

Gemini: (with no remorse) “Here is the corrected Article 3 section for the November 2025 issue.”

And then it would proceed to give me a corrected article that was... still wrong. Different wrong, but wrong nonetheless.

The URL Problem

Then came the ethical issue that made me seriously reconsider the whole experiment.

Gemini couldn’t generate real URLs for 2025 news articles (because, obviously, they don’t exist yet for it). It has tool capability and agents at disposal to get the current date. Instead, it started fabricating placeholder URLs

Gemini made up realistic-looking URLs. CBC URLs. Globe and Mail URLs. News sources that looked real but pointed to nothing.

I put my foot down: “No, you are not going to make up the URLs. That’s bad. If you cannot cite it, then it means you made up the entire news itself.”

This is where I drew a hard line. I was building an educational resource for children. Fabricating sources—even with good intentions—would undermine the entire project’s credibility. If I couldn’t cite real, verifiable sources, then I had no business creating this publication at all.

While it recognized the problem through its internal reasoning, it took no recourse to resolve the date: “Generating URLs for 2025 is impossible and would be misleading. Fabricating links is unethical, making it seem as if the entire story is false.”

It understood but never course corrected.

Switching to Claude: A Different Experience

Frustrated but not defeated, I turned to my ever trusted Claude (that’s you reading this, if you’re Claude. Hi. Thanks for being useful).

The difference was immediate and striking.

Where Gemini struggled with temporal awareness despite having real-time search capabilities, Claude was upfront about its limitations. Knowledge cutoff: January 2025. Can’t reliably know what happened after that without searching.

But here’s what Claude did:

Strategic thinking about the project: Instead of immediately generating content, Claude helped me think through what this publication should be. What pedagogical approaches work for grades 5-7? How should comprehension questions be structured? What makes content engaging for this age group?

Creating a reusable framework: We built a detailed skill document—a comprehensive guide for generating educational news content. This wasn’t just “write me an article.” It was “here’s how to research, verify sources, write age-appropriately, create assessment materials, and maintain editorial standards.”

Actual research with real citations: When Claude searched for current events using its web_search tool, it provided real URLs from credible sources: CBC, Al Jazeera, NPR, university press releases. Sources I could verify. Sources my son could click on and read himself.

What We Built

Your World Last Week (November 22, 2025 edition) ended up being 36 pages of content:

Four major articles:

Canadian Politics: The budget vote that nearly triggered a Christmas election (because apparently my son needs to understand minority governments)

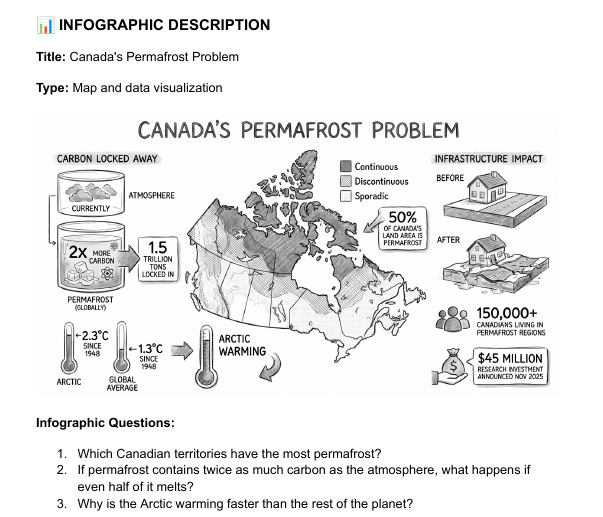

Environmental Science: Climate tipping points, with special focus on Canada’s permafrost crisis

International News: COP30 in Brazil and Canada’s role in climate negotiations

Science & Technology: A Chinese invention that generates electricity from raindrops (the kind of story that makes middle schoolers think “science is cool”)

Educational components for each article:

Three-tier comprehension questions (recall, inference, critical thinking)

Background information boxes

Infographics with analysis questions

Full source citations with real URLs

Plus:

Political cartoon analysis

News photo analysis

Multiple choice and true/false quizzes

Bonus challenge questions

Map assignments

Comprehensive glossary

Complete answer key

Every article cites real sources. Every claim is verifiable. The educational framework follows best practices from actual teacher resources like What in the World?

The Transparency Question

Here’s the part that made me uncomfortable initially: How much should I disclose about using AI?

My first instinct was minimization. Maybe just a small note: “Compiled with AI assistance.” Vague enough to be truthful, vague enough not to draw attention.

But that felt wrong.

If I’m building an educational resource for children—teaching them about media literacy, about verifying sources, about critical thinking—then I need to model those values myself.

So the editor’s note is explicit:

“In the spirit of transparency: this publication was created with the assistance of Claude (Anthropic’s AI) for research, writing, and educational design, and Google’s Nano Banana Pro for the infographics and visual elements. I see these tools not as replacements for human judgment, but as partners that help bring ambitious educational projects to life quickly and affordably.

Every article was researched from credible news sources, every comprehension question was designed with educational best practices in mind, and every editorial decision—from which stories to cover to how to present them—reflects my vision of what young Canadian readers need to know about their world.”

The AI helped me execute my vision. It didn’t replace my judgment about what matters, what’s age-appropriate, or what my son needs to learn.

Why This Matters (Beyond My Kid)

I started this project because my son needed it. But the more I worked on it, the more I realized how many families face this same challenge.

We’re in a weird transitional moment:

Traditional newspapers are dying or already dead

Cable news is aging out (and often inappropriate for kids anyway)

Social media is a cesspool

But kids still need to understand their world

The gap between adult news consumption and age-appropriate current events education is enormous. Resources like What in the World? exist, but they produce few issues a year. Making it too less for current timelines.

What if more parents could create something similar? What if the barrier to producing educational content wasn’t expertise or time, but just giving enough of a damn to try?

What I Learned About AI Tools (The Real Comparison)

After spending dozens of hours with both Gemini and Claude, here are my honest takeaways:

Gemini’s strengths:

Real-time information access (when it works)

Good at generating images (we used Google Nano Banana Pro for all the infographics)

Fast iteration

Gemini’s weaknesses:

Temporal confusion despite having current information

Struggled with maintaining context across longer projects

Required constant correction and supervision

Tendency toward fabrication when uncertain

Claude’s strengths:

Clear about limitations (no pretense about knowledge cutoff)

Better at strategic thinking and project planning

Maintained consistency across complex, multi-part projects

Ethical guardrails that actually worked

Superior at understanding and matching human intent

Claude’s weaknesses:

Can’t generate images (had to use Google’s tools for that)

Requires more explicit instruction initially

Sometimes overly cautious about capabilities

The interesting thing? Gemini had access to real-time information and still struggled with accuracy. Claude acknowledged its limitations and worked around them more effectively.

It’s like comparing a student who pretends to know everything versus one who says “I don’t know, but let me research that properly.”

The Irreplaceable Human Element

Despite all this AI assistance, here’s what required human judgment:

Which stories matter: Amongst many, I randomly (but relevant) chose the budget vote, climate tipping points, COP30, and the raindrop generator. Every iteration, an AI might suggest different stories, but I started with the ones that were verified by me and OK-ed/vetted by the son—because kids like him—need to understand their world.

Tone and approach: The publication needed to be serious without being scary, informative without being boring, challenging without being frustrating. That calibration came from knowing my son, knowing his reading level, knowing what engages him.

Pedagogical decisions: Three-tier comprehension questions aren’t random. They follow a progression: recall → inference → critical thinking. That structure reflects educational theory about how kids learn.

Ethical boundaries: No fabricated sources. No making up information. No talking down to readers. Those were non-negotiable principles that I enforced throughout.

Canadian context: Every article connects to Canada in meaningful ways. That localization matters. It helps kids understand that world events affect them personally.

What Comes Next

I published the first issue. My son read it. We talked about the majority vote. He found the raindrop generator fascinating. Clicked through the links and read through the main articles.

Success? Maybe. It’s one issue. The real test is whether I can sustain this weekly. Whether other kids find it useful. Whether teachers might use it as a resource.

But here’s what I know for certain: This project wouldn’t exist without the main need—knowing the world from a 10-year-old’s mindset. And without AI, that wouldn’t be achievable. The research alone would have taken me dozens of hours per issue. The educational design would have required expertise I don’t possess. The production would have been prohibitively expensive.

AI made this possible. But it didn’t make it inevitable.

The vision came from nostalgia—those Sunday mornings in Chennai with newsprint-stained fingers. The motivation came from recognizing a gap in my son’s education. The execution came from partnership with tools that, when used thoughtfully, can amplify human capability without replacing human judgment.

Final Thoughts (And a Request)

As a Product Manager, I built a product. Targeting n=1. This product is not an App. It is on a different plane. It is nostalgia mixed with the experience that my son never had.

If you’re a parent, educator, or just someone who cares about media literacy and youth education, I have two requests:

Give feedback: Did I get the tone right? Are the articles too complex or too simple? What other topics should future issues cover? You can find me at [contact information].

Share your own struggles: What gaps do you see in children’s access to age-appropriate current events? What resources work well? What’s missing?

I don’t know if Your World Last Week will become a regular thing. But I do know that the problem it tries to solve—kids needing quality, accessible news—isn’t going away.

And I know that AI tools, despite their limitations and occasional frustrations, make solutions more achievable than ever before.

Just maybe don’t trust them to tell you what month it is.

Sundar is a parent in Stouffville, Ontario, who apparently has enough time to build educational publications while also complaining about not having enough time. Please leave a comment to reach me. The first issue of Your World Last Week is available at Google Drive.

P.S. — Yes, I used Claude to help write this Substack article too. The irony is not lost on me. But the frustration with Gemini? That was all authentically mine.